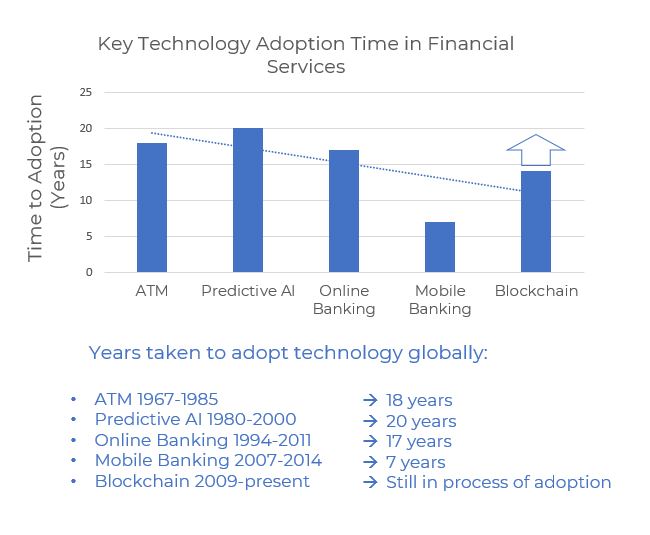

The pace of technological change in financial services has quickened significantly, putting the sector at the forefront of rolling out artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning and blockchain.

An analysis of the state of technology adoption across the financial services sector for Moore Intelligence, conducted by member firm Johnston Carmichael, concludes new digital tools offer potential to improve efficiency, boost margins and reduce customer complaints – but the opportunities also present risks, that unless understood and mitigated, may outweigh the benefits.

For an industry established three centuries ago, the advances of the past 25 years have spawned nimble challengers with new products which have forced established players and regulators to fundamentally change their focus and operating models.

“Technologies, from smartphone apps to blockchain, have fundamentally changed the way financial services are delivered, enabling customers to choose from a wider range of financial products and make decisions faster than ever before,” says Ewen Fleming, head of consulting at Johnston Carmichael and leader of Moore Global financial services group.

“We now find ourselves in a new era where the time taken to adopt new technology has accelerated. That brings both opportunities and risks which are less predictable than before.”

Research into what we now call AI first emerged in the 1950s (along with credit cards) but adoption was slow and customers saw few practical applications. As the millennium approached big technical advances in Silicon Valley expanded computing power and ushered in rapid development of financial technology, or fintech.

Between 1995 and 2014 there have been significant technical advances impacting on financial services, from online banking to contactless credit cards

The main impetus for this change has been customer demand for online banking that has forced changes in distribution of their services, data collection and protection and fraud prevention. Financial companies also needed to improve efficiency in customer service and bolster lacklustre profit margins and returns to their investors.

Additionally, some traditional financial companies also chose to recast themselves as tech innovators or create digital-driven subsidiaries or brands to rejuvenate themselves and persuade the market to rate their shares more highly and raise their valuations.

Opportunities to improve the accuracy and efficiency of operations are powerful drivers for financial companies:

• AI can gather and process banking data and produce recommendations about new products or services that could help customers with financial issues in their lives.

• Machine learning algorithms can analyse customer transaction data to identify patterns of fraudulent activity and also use behavioural biometrics, such as fingerprint or facial recognition, to detect and prevent suspicious activity.

• Fund managers are using the mountains of new data that can be accessed and analysed in seconds by AI to assess potential risks to company performance that may not be immediately obvious, such as the impact of poor governance or lack of sustainability measures to respond to the ESG agenda.

• Insurers are using the technology to build ever more accurate models of climate change in order to rate the risks to the assets they underwrite from rising sea levels and more volatile storm patterns.

However, greater reliance on data requires the information inputted to be 100% accurate – and that is open to question.

“We are in a new era where the time taken to adopt new technology has accelerated. That brings both opportunity and risks, many less predictable than previously.”

Ewen Fleming

Leader of Moore Global Financial Services

.png)

“We know of one situation where a bank flagged around 1% of its customers as vulnerable, but when AI algorithms were applied that figure shot up to around 35%,” says Fleming. “The problem is we do not yet have complete confidence in the quality of the information and ability to reliably remove false positives.

Another much-vaunted technological advance that is already delivering benefits is blockchain – although the origins of the technology can traced back 30 years. While most commonly associated with crypto currency, it has much wider applications throughout financial services where sensitive material has to be shared and stored securely.

Blockchain can streamline banking and lending services to reduce counter-party risk, improve issuance and settlement times and enable real-time verification of financial documents.

By establishing a decentralised ledger for payments, blockchain technology facilitates faster payments at lower fees than banks. These cloud-based clearance and settlement systems can reduce operational costs and bring us closer to real-time transactions between financial institutions.

However, there are questions over the ability to scale up blockchain platforms. Visa, a world leader in electronic payments, can process 1,700 transactions per second – blockchain can currently only manage an average of 4.6.

Part of the problem is the fragmentation and lack of standardised protocols which limits the seamless transfer of assets and data between different blockchain ecosystems.

Another issue for blockchain and the artificial intelligence associated with it is the sheer amount of power they consume in these climate-conscious times. Training just one AI model can emit more than 626,00 pounds (284,000kg) of carbon dioxide.

These are, at least, known challenges and can be tackled with further research and development. However, whether the investment in new technology and its application delivers an acceptable rate of return for investors will depend on the future – and still largely unknown – shape of the legislative framework.

.png)

Potential increase in global GDP driven by regenerative artificial intelligence like ChatGPT

.png)

Regulators have been slow to catch up with the pace of technological innovation but in June the European Parliament approved the European Union’s AI Act which could lead to the world’s first formal regulation of the technology after further consultation with the EU’s other institutions.

A major plank of that legislation impacts generative AI, which can write essays, produce new versions of Shakespeare and write hit songs in the style of long-dead musicians. It is the technology behind tools like ChatGPT but under the proposed EU rules, new systems using regenerative AI must be reviewed by a panel before commercial release and real-time facial recognition would be banned.

Two months before the European Parliament vote Goldman Sachs released a report suggesting generative artificial intelligence could drive a 7% increase in global GDP worth $7 trillion. If other countries follow the EU lead that forecast could turn out to be over-optimistic.

“When technology advances rapidly then regulation understandably lags behind,” says Ewen Fleming. “When regulation does catch up it can however go too far, and that represents a material risk to committed investment. It can also dampen further innovation as regulations are revised in the following years to make it more proportionate and relevant.”

If the first part of the technology revolution in financial services took five decades to unfold, the next phase might only take five years. The pressure on technology developers, investors and regulators to keep up with this pace of change will be intense.